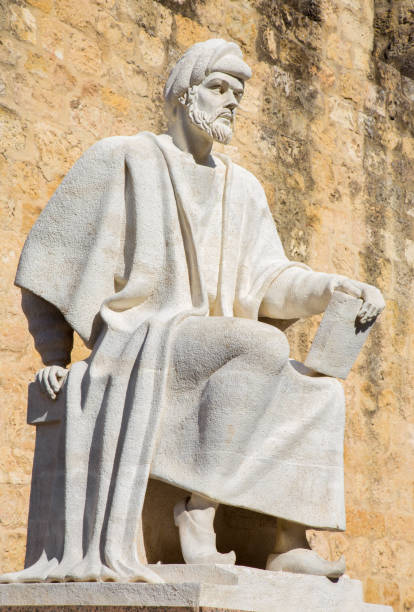

Like Christianity in the West, Islam grappled with the conflict between revealed truth (revelation) and reason (philosophy). Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd (1126–1198 CE), known in the West as Averroes and referred to as ‘the Commentator’ for his extensive glosses on Aristotle’s works, addressed this challenge in his treatise On the Harmony of Religions and Philosophy. In this work, Ibn Rushd argued that religion and philosophy were not inherently in conflict but were, in fact, compatible and complementary. Beyond philosophy, Ibn Rushd wrote extensively on a range of subjects, including jurisprudence and medicine, showcasing his intellectual versatility. His writings had a profound impact on Europe, where they were widely read by medieval philosophers and eventually integrated into university curricula.

As you read the selection below, consider the following questions:

- Why and how does philosophy bring its student to a closer understanding of the Creator?

- Why does Ibn Rushed conclude that the Law makes the observation and consideration of creation by reason obligatory?

- Does Ibn Rushd use the content of the Qur’an to support his position that philosophy and religion can be both studied?

Complete the Primary Source Analysis Form when finished.

Source: This text is part of the Internet Medieval Source Book.

On the Harmony of Religions and Philosophy (Excerpts)

Introduction

We maintain that the business of philosophy is nothing other than to look into creation and to ponder over it in order to be guided to the Creator — in other words, to look into the meaning of existence. For the knowledge of creation leads to the cognizance of the Creator, through the knowledge of the created. The more perfect becomes the knowledge of creation, the more perfect becomes the knowledge of the Creator. The Law encourages and exhorts us to observe creation. Thus, it is clear that this is to be taken either as a religious injunction or as something approved by the Law. But the Law urges us to observe creation by means of reason and demands theknowledge thereof through reason. This is evident from different verses of the Qur’an. Forexample, the Qur’an says: “Wherefore take example from them, you who have eyes” [Qur’an49.2]. That is a clear indication of the necessi-ty of using the reasoning faculty, or rather both reason and religion, in the interpretation of things. Again it says: “Or do they not contemplate the kingdom of heaven and earth and the things which God has created” [Qur’an 7.184]. This is in plain exhortation to encourage the use of observation of creation. And remember that one whom God especially distinguishes in this respect, Abraham, the prophet. For He says: “And this did we show unto Abraham: the kingdom of heaven and earth” [Qur’an 6.75]. Further, He says: “Do they not consider the camels, how they are created; and the heaven, how it is raised” [Qur’an 88.17]. Or, still again: “And (who) meditate on the creation of heaven and earth, saying, O Lord you have not created this in vain” [Qur’an 3.176]. There are many other verses on this subject: too numerous to be enumerated.

Now, it being established that the Law makes the observation and consideration of creation by reason obligatory — and consideration is nothing but to make explicit the implicit — this can only be done through reason. Thus we must look into creation with the reason. Moreover, it is obvious that the observation which the Law approves and encourages must be of the most perfect type, performed with the most perfect kind of reasoning. As the Law emphasizes the knowledge of God and His creation by inference, it is incumbent on any who wish to know God and His whole creation by inference, to learn the kinds of inference, their conditions and that which distinguishes philosophy from dialectic and exhortation from syllogism. This is impossible unless one possesses knowledge beforehand of the various kinds of reasoning and learns to

distinguish between reasoning and what is not reasoning. This cannot be done except one knows its different parts, that is, the different kinds of premises.

Hence, for a believer in the Law and a follower of it, it is necessary to know these things before he begins to look into creation, for they are like instruments for observation. For, just as a student discovers by the study of the law, the necessity of knowledge of legal reasoning with all its kinds and distinctions, a student will find out by observing the creation the necessity of metaphysical reasoning. Indeed, he has a greater claim on it than the jurist. For if a jurist argues the necessity of legal reasoning from the saying of God: “Wherefore take example from them O you who have eyes” [Qur’an 59.2], a student of divinity has a better right to establish the same from it on behalf of metaphysical reasoning.

One cannot maintain that this kind of reasoning is an innovation in religion because it did not exist in the early days of Islam. For legal reasoning and its kinds are things which were invented also in later ages, and no one thinks they are innovations. Such should also be our attitude towards philosophical reasoning. There is another reason why it should be so, but this is not the proper place to mention it. A large number of the followers of this religion confirm philosophical reasoning, all except a small worthless minority, who argue from religious ordinances. Now, as it is established that the Law makes the consideration of philosophical reasoning and its kinds as necessary as legal reasoning, if none of our predecessors has made an effort to enquire into it, we should begin to do it, and so help them, until the knowledge is complete. For if it is difficult or rather impossible for one person to acquaint himself single-handed with all things which it is necessary to know in legal matters, it is still more difficult in the case of philosophical

reasoning. And, if before us, somebody has enquired into it, we should derive help from what he

has said. It is quite immaterial whether that man is our co-religionist or not; for the instrument by

which purification is perfected is not made uncertain in its usefulness by its being in the hands of

one of our own party, or of a foreigner, if it possesses the attributes of truth. By these latter we

mean those Ancients who investigated these things before the advent of Islam.

Now, such is the case. All that is wanted in an enquiry into philosophi-cal reasoning has already

been perfectly examined by the Ancients. All that is required of us is that we should go back to

their books and see what they have said in this connection. If all that they say be true, we should

accept it and if there be something wrong, we should be warned by it. Thus, when we have

finished this kind of research we shall have acquired instruments by which we can observe the

universe, and consider its general character. For so long as one does not know its general

character one cannot know the created, and so long as he does not know the created, he cannot

know its nature.

All things have been made and created. This is quite clear in itself, in the case of animals and plants, as God has said “Verily the idols which you invoke, beside God, can never create a single fly, though they may all assemble for that purpose” [Qur’an 22.72]. We see an inorganic substance and then there is life in it. So we know for certain that there is an inventor and bestower of life, and He is God. Of the heavens we know by their movements, which never become slackened, that they work for our benefit by divine solicitude, and are subordinate to our welfare. Such an appointed and subordinate object is always created for some purpose. The second principle is that for every created thing there is a creator. So it is right to say from the two foregoing principles that for every existent thing there is an inventor. There are many arguments, according to the number of the created things, which can be advanced to prove this premise. Thus, it is necessary for one who wants to know God as He ought to be known to acquaint himself with the essence of things, so that he may get information about the creation of all things. For who cannot understand the real substance and purpose of a thing, cannot understand the minor meaning of its creation. It is to this that God refers in the following verse “Or do they not contemplate the heaven and the earth, and the things which God has created?” [Qur’an 7.184]. And so a man who would follow the purpose of philosophy in investigating the existence of things, that is, would try to know the cause which led to its creation, and the purpose of it would know the argument of kindness most perfectly. These two arguments are those adopted by Law.

The verses of the Qur’an leading to a knowledge of the existence of God are dependent only on the two foregoing arguments. It will be quite clear to anyone who will examine closely the verses, which occur in the Divine Book in this connection. These, when investigated, will be found to be of three kinds: either they are verses showing the “arguments of kindness,” or those mentioning the “arguments of creation, ” or those which include both the kinds of arguments. The following verses may be taken as illustrating the argument of kindness. “Have we not made the earth for a bed, and the mountains for stakes to find the same? And have we not created you of two sexes; and appointed your sleep for rest; and made the night a garment to cover you; and destined the day to the gaining of your livelihood and built over you seven solid heavens; and placed therein a burning lamp? And do we not send down from the clouds pressing forth rain,

water pouring down in abundance, that we may thereby produce corn, and herbs, and gardens planted thick with trees?” [Qur’an 77.6-16] and, “Blessed be He Who has placed the twelve signs in the heavens; has placed therein a lamp by day, and the moon which shines by night” [Qur’an 25.62] and again, “Let man consider his food” [Qur’an 80.24].

The following verses refer to the argument of invention, “Let man consider, therefore of what he is created. He is created of the seed poured forth, issuing from the loins, and the breast bones” [Qur’an 86.6]; and, “Do they not consider the camels, how they are created; the heaven, how it is raised; the mountains, how they are fixed; the earth how it is extended” [Qur’an 88.17]; and again “O man, a parable is propounded unto you; wherefore hearken unto it. Verily the idols which they invoke, besides God, can never create a single fly, though they may all assemble for the purpose” [Qur’an 22.72]. Then we may point to the story of Abraham, referred to in the following verse, “I direct my face unto Him Who has created heaven and earth; I am orthodox, and not of the idolaters” [Qur’an 6.79]. There may be quoted many verses referring to this argument. The verses comprising both the arguments are also many, for instance, “O men, of

Mecca, serve your Lord, Who has created you, and those who have been before you: peradventure you will fear Him; Who has spread the earth as a bed for you, and the heaven as a covering, and has caused water to descend from heaven, and thereby produced fruits for your sustenance. Set not up, therefore, any equals unto God, against your own knowledge [Qur’an 2.19]. His words, “Who has created you, and those who have been before you,” lead us to the argument of creation; while the words, “who has spread the earth” refer to the argument of divine solicitude for man. Of this kind also are the following verses of the Qur’an, “One sign of the resurrection unto them is the dead earth; We quicken the same by rain, and produce therefrom various sorts of grain, of which they eat” [Qur’an 36.32]; and, “Now in the creation of heaven and earth, and the vicissitudes of night and day are signs unto those who are endowed with understanding, who remember God standing, and sitting, and lying on their sides; and meditate on the creation of heaven and earth, saying O Lord, far be it from You, therefore deliver us from the torment of hellfire” [Qur’an 3.188]. Many verses of this kind comprise both the kinds of arguments.

This method is the right path by which God has invited men to a knowledge of His existence, and informed them of it through the intelligence which He has implanted in their nature. The following verse refers to this fixed and innate nature of man, “And when the Lord drew forth their posterity from the loins of the sons of Adam, and took them witness against themselves, Am I not your Lord? They answered, Yes, we do bear witness” [Qur’an 7.171]. So it is incumbent for one who intends to obey God, and follow the injunction of His Prophet, that he should adopt this method, thus making himself one of those learned men who bear witness to the divinity of God, with His own witness, and that of His angels, as He says, “God has borne

witness, that there is no God but He, and the angels, and those who are endowed with wisdom profess the same; who execute righteousness; there is no God but He; the Mighty, the Wise” [Qur’an 3.16]. Among the arguments for both of themselves is the praise which God refers to in the following verse, “Neither is there anything which does not celebrate his praise; but you understand not their celebration thereof” [Qur’an 17.46].

It is evident from the above arguments for the existence of God that they are dependent upon two categories of reasoning. It is also clear that both of these methods are meant for particular people; that is, the learned. Now as to the method for the masses. The difference between the two lies only in details. The masses cannot understand the two above-mentioned arguments but only what they can grasp by their senses; while the learned men can go further and learn by reasoning also, besides learning by sense. They have gone so far that a learned man has said, that the benefits the learned men derive from the knowledge of the members of human and animal body are a thousand and one. If this be so, then this is the method which is taught both by Law and by Nature. It is the method which was preached by the Prophet and the divine books. The learned men do not mention these two lines of reasoning to the masses, not because of their number, but because of a want of depth of learning on their part about the knowledge of a single thing only. The example of the common people, considering and pondering over the universe, is like a man

who looks into a thing, the manufacture of which he does not know. For all that such a man can know about it is that it has been made, and that there must be a maker of it. But, on the other hand, the learned look into the universe, just as a man knowing the art would do; try to understand the real purpose of it. So it is quite clear that their knowledge about the Maker, as the maker of the universe, would be far better than that of the man who only knows it as made. The atheists, who deny the Creator altogether, are like men who can see and feel the created things, but would not acknowledge any Creator for them, but would attribute all to chance alone, and that they come into being by themselves.

Now, then, if this is the method adopted by the Law, it may be asked: What is the way of proving the unity of God by means of the Law; that is, the knowledge of the religious formula that “there is no god, but God. ” The negation contained in it is an addition to the affirmative, which the formula contains, while the affirmative has already been proved. What is the purpose of this negation? We would say that the method, adopted by the Law, of denying divinity to all but God is according to the ordinance of God in the Qur’an. . .

If you look a little intently it will become clear to you, that in spite of the fact that the Law has not given illustration of those things for the common people, beyond which their imagination cannot go, it has also informed the learned men of the underlying meanings of those illustrations. So it is necessary to bear in mind the limits which the Law has set about the instruction of every class of men, and not to mix them together. For in this manner the purpose of the Law is multiplied. Hence it is that the Prophet has said, “We, the prophets, have been commanded to adapt ourselves to the conditions of the people, and address them according to their intelligence.” He who tries to instruct all the people in the matter of religion, in one and the same way, is like a man who wants to make them alike in actions too, which is quite against apparent laws and reason.

From the foregoing it must have become clear to you that the divine vision has an esoteric meaning in which there is no doubt, if we take the words of the Qur’an about God as they stand, that is, without proving or disproving the anthropomorphic attribute of God. Now since the first part of the Law has been made quite clear as to God’s purity, and the quantity of the teaching fit for the common people; it is time to begin the discussion about the actions of God, after which our purpose in writing this treatise will be over. In this section we will take up five questions around which all others in this connection revolve. In the first place a proof of the creation of the universe; secondly, the advent of the prophets; thirdly, predestination and fate; fourthly, Divine justice and injustice; and fifthly, the Day of Judgment