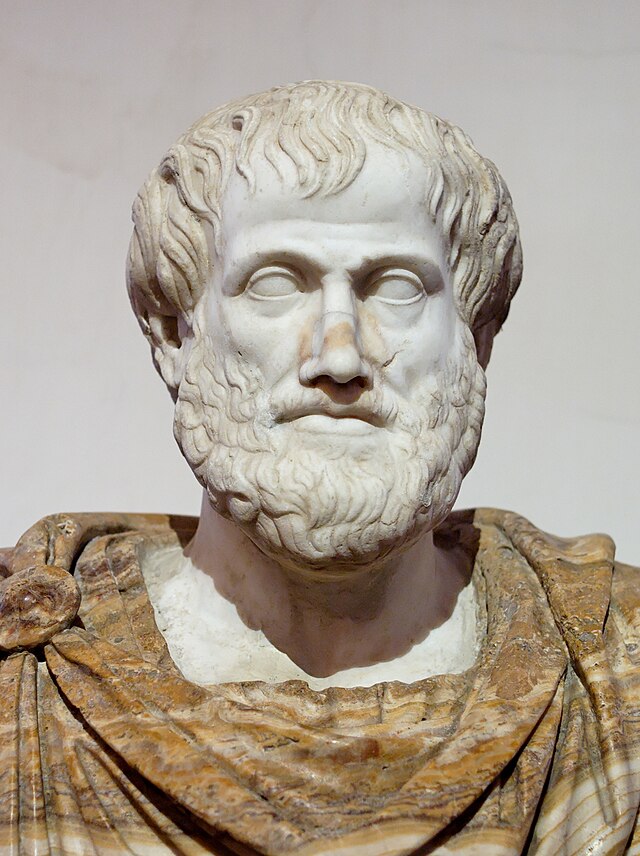

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was one of the most influential and prolific Greek philosophers of his time. His extensive writings covered a wide range of topics, including logic, metaphysics, ethics, and political theory, leaving an enduring impact on thinkers from Late Antiquity through the Renaissance. In his Metaphysics, one of his principal works, Aristotle described its subject matter as ‘first philosophy,’ or the study of wisdom. This foundational text explores fundamental questions about existence, causality, and the nature of being.

As you read the selections below, consider the following questions:

- What is wisdom?

- What purpose does wisdom serve?

- How does he define a wise man?

Complete the Primary Source Analysis Form when finished.

Source: http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/metaphysics.1.i.html

Metaphysics Book I (Selections)

“All these examples show, then, that recollection is caused by like things and also by unlike things, do they not?”

“Yes.”

“And when one has a recollection of anything caused by like things, will he not also inevitably consider whether this recollection offers a perfect likeness of the thing recollected, or not?”

“Inevitably,” he replied.

“Now see,” said he, “if this is true. We say there is such a thing as equality. I do not mean one piece of wood equal to another, or one stone to another, or anything of that sort, but something beyond that—equality in the abstract. Shall we say there is such a thing, or not?”

“We shall say that there is,” said Simmias, “most decidedly.”

“And do we know what it is?”

“Certainly,” said he.

“Whence did we derive the knowledge of it? Is it not from the things we were just speaking of? Did we not, by seeing equal pieces of wood or stones or other things, derive from them a knowledge of abstract equality, which is another thing? Or do you not think it is another thing? Look at the matter in this way. Do not equal stones and pieces of wood, though they remain the same, sometimes appear to us equal in one respect and unequal in another?”

“Certainly.”

“Well, then, did absolute equals ever appear to you unequal or equality inequality?”

“No, Socrates, never.”

“Then,” said he, “those equals are not the same as equality in the abstract.”

“Not at all, I should say, Socrates.”

“But from those equals,” said he, “which are not the same as abstract equality, you have nevertheless conceived and acquired knowledge of it?”

“Very true,” he replied.

“And it is either like them or unlike them?”

“Certainly.”

“It makes no difference,” said he. “Whenever the sight of one thing brings you a perception of another, whether they be like or unlike, that must necessarily be recollection.”

“Surely.”

“Now then,” said he, “do the equal pieces of wood and the equal things of which we were speaking just now affect us in this way: Do they seem to us to be equal as abstract equality is equal, or do they somehow fall short of being like abstract equality?”

“They fall very far short of it,” said he.

“Do we agree, then, that when anyone on seeing a thing thinks, ‘This thing that I see aims at being like some other thing that exists, but falls short and is unable to be like that thing, but is inferior to it, he who thinks thus must of necessity have previous knowledge of the thing which he says the other resembles but falls short of?”

“We must.”

“Well then, is this just what happened to us with regard to the equal things and equality in the abstract?”

“It certainly is.“

“Then we must have had knowledge of equality before the time when we first saw equal things and thought, ‘All these things are aiming to be like equality but fall short.’”

“That is true.”

“And we agree, also, that we have not gained knowledge of it, and that it is impossible to gain this knowledge, except by sight or touch or some other of the senses? I consider that all the senses are alike.”

“Yes, Socrates, they are all alike, for the purposes of our argument.”

“Then it is through the senses that we must learn that all sensible objects strive after absolute equality and fall short of it. Is that our view?”

“Yes.”

“Then before we began to see or hear or use the other senses we must somewhere have gained a knowledge of abstract or absolute equality, if we were to compare with it the equals which we perceive by the senses, and see that all such things yearn to be like abstract equality but fall short of it.”

“That follows necessarily from what we have said before, Socrates.”

“And we saw and heard and had the other senses as soon as we were born?”

“Certainly.”

“But, we say, we must have acquired a knowledge of equality before we had these senses?”

“Yes.

“Then it appears that we must have acquired it before we were born.”

“It does.”

“Now if we had acquired that knowledge before we were born, and were born with it, we knew before we were born and at the moment of birth not only the equal and the greater and the less, but all such abstractions? For our present argument is no more concerned with the equal than with absolute beauty and the absolute good and the just and the holy, and, in short, with all those things which we stamp with the seal of absolute in our dialectic process of questions and answers; so that we must necessarily have acquired knowledge of all these before our birth.”

“That is true.”

“And if after acquiring it we have not, in each case, forgotten it, we must always be born knowing these things, and must know them throughout our life; for to know is to have acquired knowledge and to have retained it without losing it, and the loss of knowledge is just what we mean when we speak of forgetting, is it not, Simmias?”

“Certainly,“